------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Chesapeake & Ohio Railway traces its origin to the Louisa Railroad of

Louisa County, Virginia, begun in 1836,

and the James River & Kanawha Canal

Company begun 1785, also in Virginia. The C&O of the 1950s and 1960s at its

height before the first modern merger, was the product of about 150 smaller

lines that had been incorporated into the system over time.

By 1850 the Louisa Railroad had been built east to Richmond and west to

Charlottesville,

By 1850 the Louisa Railroad had been built east to Richmond and west to

Charlottesville,

and in keeping with its new and larger vision, was renamed

Virginia Central. The Commonwealth of Virginia,

always keen to help with "internal improvements" not only owned a portion of

Virginia Central stock, but incorporated

and financed the

Blue Ridge Railroad to accomplish the hard and expensive task of crossing

the first mountain barrier

to the west. Under the leadership of the great early

civil engineer Claudius Crozet, the Blue Ridge Railroad

built over the mountain, using four tunnels, including the 4,263-foot Blue Ridge Tunnel at the top of the

mountain,

then one of the longest tunnels in the world.

While the Blue Ridge Railroad attacked the mountains, Virginia Central was

building westward from the west foot of the mountains.

It crossed the Great

Valley of Virginia, The Shenandoah, and the Shenandoah range Great North

Mountain,

reaching a point known as Jackson's River Station at the foot of

Alleghany Mountain in 1856.

This is the site that would later be called Clifton

Forge.

To finish its line across the mountainous territory of the Alleghany Plateau

known in old Virginia as the "Transmountaine",

To finish its line across the mountainous territory of the Alleghany Plateau

known in old Virginia as the "Transmountaine",

the Commonwealth again chartered

a state-subsidized railroad called the Covington & Ohio.

This company completed

important grading work on the Alleghany grade and did

considerable work on numerous tunnels over the mountain

and westward. It also

did a good deal of roadbed work around Charleston on the Kanawha River.

Then the

War Between the States intervened, and work was stopped on the westward

expansion.

During the Civil War the Virginia Central was one of the Confederacy's most

important lines, carrying food from t

he Shenandoah region to Richmond, and

ferrying troops and supplies back and forth as the campaigns frequently

surrounded

its tracks. On more than one occasion it was used in actual tactical

operations, transporting troops directly to the battlefield.

But, it was a prime

target for Federal armies, and by the end of the war had only about

five miles

of track still in operation, and $40 in gold in its treasury.

Following the war, Virginia Central officials realized that they would have to

get capital to rebuild

Following the war, Virginia Central officials realized that they would have to

get capital to rebuild

from outside the economically devastated South and

attempted to attract British interests, without success.

Finally, they succeeded

in getting Collis P. Huntington of New York interested in the line. He is, of

course,

the same Huntington that was one of the "big Four" involved in building

the Central Pacific portion of the

Transcontinental Railroad, which was at this

time just reaching completion. Huntington had a vision of a

true

transcontinental that would go from sea to sea under one operating management,

and decided that the

Virginia Central might be the eastern link to this system.

Huntington supplied the Virginians with the money needed to complete the line

to the Ohio River,

through what was now the new state of West Virginia. The old

Covington & Ohio's properties were

conveyed to the

Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad in keeping with its new mission of linking the

Tidewater

coast of Virginia with the "Western Waters" of the Ohio River. This

was the old dream of the

"Great Connection" which had been current in Virginia

since Colonial times.

On July 1, 1867 the C&O was completed nine miles from Jackson's River Station to

the town of Covington,

On July 1, 1867 the C&O was completed nine miles from Jackson's River Station to

the town of Covington,

seat of Alleghany County, Virginia. By 1869, it had

crossed Alleghany Mountain, using much of the tunneling and

roadway work done by

the Covington & Ohio before the war, and was running to the great mineral

springs resort at

White Sulphur Springs, now in Greenbrier County, West

Virginia. Here stagecoach connections were made for

Charleston and the

navigation on the Kanawha River and thus water transportation on the whole

Ohio/Mississippi system.

During 1869-1873 the hard work of building through West Virginia was done

with large crews working

from the new city of Huntington on the Ohio River and

White Sulphur much as the UP and CP had

done in the transcontinental work, and

the line was joined at Hawks Nest, WV on January 28, 1873.

Collis Huntington intended to connect the C&O with his Western and Mid-Western

holdings,

Collis Huntington intended to connect the C&O with his Western and Mid-Western

holdings,

but had much other railroad construction to finance and he stopped the

line at the Ohio River. Over the next

few years he did little to improve its

rough construction or develop traffic. The only connection to the West was

by

packet boats operating on the Ohio River. Because the great mineral resources of

the region hadn't been fully

realized yet, the C&O suffered through the bad

times brought on by the financial panic Depression of 1873, and

went into

receivership in 1878. When reorganized it was renamed The

Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Company.

During the ten years 1878-1888 C&O's coal resources began to be developed and

shipped eastward.

In 1881 the Peninsula Subdivision was completed from Richmond

to the new city of Newport News

located on Hampton Roads, the East's largest

ice-free port. Transportation of coal to Newport News

where it was loaded on

coastwise shipping and transported to the Northeast became a staple

of the C&O's

business at this time.

In 1888 Huntington lost control of the C&O. A reorganization without foreclosure

resulted

In 1888 Huntington lost control of the C&O. A reorganization without foreclosure

resulted

in his losing his majority interest to the Morgan and Vanderbilt

interests, which installed Melville E. Ingalls

as President. Ingalls was, at the

time, President of the Vanderbilt's Chicago, Cleveland, Cincinnati & Louisville,

The "Big Four System", and held both presidencies concurrently for the next

decade. Ingalls installed

George W. Stevens as general manager and effective

head of the C&O.

In 1889 the Richmond & Alleghany Railroad, which had been built along the

tow-path of the defunct

James River & Kanawha Canal, was merged into the C&O,

giving it a down grade "water level"

line from Clifton Forge to Richmond, avoiding the heavy grades of North Mountain and the Blue Ridge

on the original

Virginia Central route. This "James River Line"

remains the principal artery of

coal transportation to the present day.

Ingalls and Stevens completely rebuilt the C&O to "modern" standards with

ballasted roadbed,

enlarged and lined tunnels, steel bridges, and heavier steel

rails, as well as new, larger cars and locomotives.

In 1888 the C&O built the Cincinnati Division from Huntington down the South

bank of the Ohio River and

across the river at Cincinnati, connecting with the

"Big Four" and other Midwestern Railroads.

From 1900 to 1920 most of the C&O's line tapping the rich bituminous coal

fields of southern West Virginia

and eastern Kentucky were built, and the C&O as

it was known throughout the rest of the

20th Century was essentially in place.

In 1910 C&O merged the Chicago, Cincinnati & Louisville Railroad into its

system.

This line had been built diagonally across the state of Indiana from

Cincinnati to Hammond

in the preceding decade. This gave the C&O a direct line

from Cincinnati

to the great railroad hub of Chicago.

Also in 1910 C&O interests bought control of the Kanawha & Michigan and Hocking

valley lines in Ohio,

Also in 1910 C&O interests bought control of the Kanawha & Michigan and Hocking

valley lines in Ohio,

with a view to connecting with the Great Lakes through

Columbus. Eventually Anti-trust laws forced C&O to abandon

its K&M interests, but it was allowed to retain the Hocking valley, which operated about 350 miles

in Ohio, including

a direct line from Columbus to the port of Toledo, and

numerous branches southeast of Columbus in the Hocking Coal Fields.

But there

was no direct connection with the C&O's mainline, now hauling previously

undreamed-of quantities of coal.

To get its coal up to Toledo and into Great

Lakes shipping, C&O contracted with its rival Norfolk & Western to haul trains

from Kenova, WV to Columbus. N&W, however, limited this business and the

arrangement was never satisfactory.

C&O gained access to the Hocking Valley by building a new line directly from

a point a few miles from its huge

and growing terminal at Russell, KY to

Columbus between 1917 and 1926. It crossed the Ohio River at Limeville, KY.

to Sciotoville, Ohio, on the great Limeville or Sciotoville bridge which remains

today the mightiest bridge every built

from point of view of its load capacity.

Truly a monument to engineering, but seldom commented on outside

engineering

circles because of its relatively remote location.

With the connection at Columbus complete, C&O soon was sending more of its

high quality metallurgical

and steam coal west than East, and in 1930 it merged

the Hocking Valley into its system.

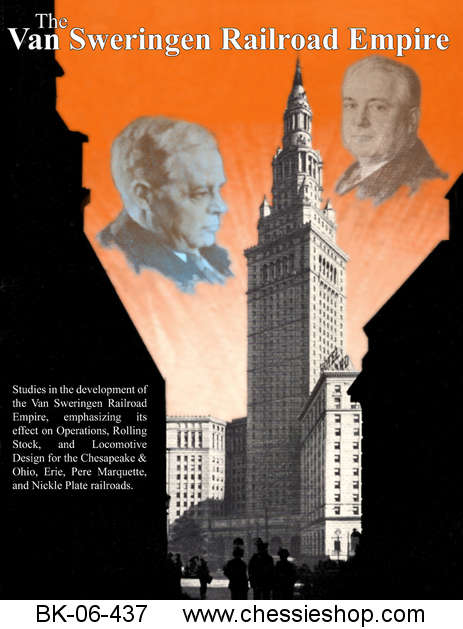

The next great change for C&O came in 1923 when the great Cleveland

financiers, the brother 0. P.

The next great change for C&O came in 1923 when the great Cleveland

financiers, the brother 0. P.

and M. J. Van Sweringen, bought controlling

interest in the line as part of their expansion of the Nickel Plate Road NKP

system. Eventually they controlled the NKP, C&O, Pere Marquette Railway in

Michigan and Ontario, and Erie Railroads.

They managed to control this huge

system by a maze of holding companies and interlocking directorships. This house

of cards

tumbled when the Great Depression began and the Van Sweringen companies

collapsed. But the C&O was a strong line and

despite the fact that in the early

1930s over 50% of American railroads went into receivership, it not only avoided

bankruptcy, but took the occasion of cheap labor and materials to again

completely rebuild itself.

During the early 1930s when it seemed the whole country was retrenching, C&O

was boring new tunnels, adding double track,

rebuilding bridges, upgrading the

weight of its rail, and rebuilding its roadbed, all with money from its

principal commodity

of haulage: Coal. Even in the hard years of the Depression

coal was something that had to be used everywhere,

and C&O was sitting astride

the best bituminous seams in the country.

Because of this great upgrading and building program, C&O was in prime

condition to carry the monumental loads

needed during World War II. During the

War it transported men and materiel in unimagined quantities as the United

States

used the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation as a principal departure point

for the European Theater. The invasion of

North Africa was loaded here. Of

course coal was needed in ever increasing quantities by war industries, and C&O

was ready with a powerful, well organized, well maintained railway powered by

the largest and most modern locomotives.

By the end of the war C&O was poised to help America during its great growth

during

By the end of the war C&O was poised to help America during its great growth

during

the decades following, and at mid-century was truly a line of national

importance. It became

more so, at least in the public's eye through Robert R.

Young, its mercurial Chairman.

Young got control of the C&O through the remnants of the Van Sweringen

companies in 1942, and for the

next decade he became "the gadfly of the rails,"

as he challenged old methods of financing and operating railroads,

and

inaugurated many forward looking advances in technology that have ramifications

to the present. He changed the C&O's

herald or logo to "C&O for Progress" to

embody his ideas that C&O would lead the industry to a new day. He installed

a

well-staffed research and development department that came up with ideas for

passenger service that are thought

to be futuristic even now, and for freight

service that would challenge the growth of trucking. Young eventually gave

up

his C&O position to become Chairman of the New York Central before his untimely

death in 1958.

During the Young era and following, C&O was headed by Walter J. Tuohy, under

whose control the "For Progress"

theme continued, though in a more muted way

after the departure of Young. During this time C&O installed the first

large

computer system in railroading, developed larger and better freight cars of all

types, switched reluctantly from

steamto diesel motive power, and diversified

its traffic, which had already occurred in 1947 when it merged into the

system

the old Pere Marquette Railway of Michigan and Ontario which had been controlled

since Van Sweringen days.

The PM's huge automotive industry traffic, taking raw

materials in and finished vehicles out, gave C&O some protection

from the swings

in the coal trade, putting merchandise traffic at 50% of the company's haulage.

C&O continued to be one of the most profitable and financially sound railways

in America, and in 1963 started the modern

merger era by "affiliating" with the

ancient modern of railroads, the hoary Baltimore & Ohio. Avoiding a mistake that

would

become endemic to later mergers among other lines, a gradual amalgamation

of the two lines' services, personnel, motive

power and rolling stock, and

facilities built a new and stronger system, which was ready for a new name in

1972.

Under the leadership of the visionary Hays T. Watkins, the C&O, B&O and

Western Maryland became Chessie System,

taking on the name officially that had

been used colloquially for so long for the C&O,

after the mascot kitten used in

ads since 1934.

Under Watkins' careful and visionary leadership Chessie System then merged

with Seaboard System, itself a combination

of great railroads of the Southeast

including Seaboard Air Line Railway, Atlantic Coast Line,

Louisville &

Nashville, Clinchfield, and others, to form a new mega-railroad: CSX.

Today, CSX, after taking on 43% of Conrail, is one of four major railroad

systems left in the country. It is still an

innovative leader, true to its roots

in Robert Young and "For Progress," the Van Sweringens and their quest for

efficiency

and standardization, to George Stevens and his dedication to

operating efficiency and safety awareness, back to

Collis Huntington and his

dreams of a transportation empire, and even back to those long forgotten

Virginians who started

it all to c their farm produce to market in the

1830's in a different world, the world before the Railroad.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Pictures and Story from Chesapeake and Ohio Historical Society

[ Back ]