|

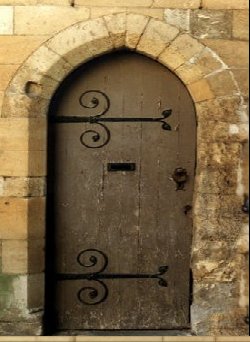

Doors Back -------------------- -------------------- -------------------- Last Hanging in Huntington 1892 -------------------- Barboursville -------------------- --------------------

|

|

|

Doors to the Past |

|

Merritt Cemetery

Excavating Clues to the Past

By Sheila McEntee

It is a fairly typical day in the offices of Horizon Research Consultants, Inc. (HRC) in Morgantown. The telephone rings continually, staff members come and go, and the steady clicking of a computer keyboard signals intensive data entry. Amid this bustle of activity, at a long conference table, HRC president Gloria Gozdzik, staff archeologist Chip Connelly, and historic archeologist Sue Bergeron examine several prehistoric artifacts found during a recent excavation. The artifacts, which have been carefully sorted, washed, and catalogued, include ancient tools, projectile points, and shards of pottery. Each holds clues to the lives of Native Americans who roamed, lived, and traded near modern-day Barboursville, West Virginia. "When you begin to put the pieces together, that's the fun stuff. That's what we like to do," says Gozdzik, an archeologist and anthropologist who founded HRC, an archeological consulting and cultural resource management company, in 1983.

Since founding her company, Gozdzik, who also is an adjunct assistant professor in the Sociology and Anthropology Department at West Virginia University, has led numerous archeological investigations and surveys for both private companies and public agencies, to help them comply with federal and state laws related to the preservation of historic structures, archeological sites, and other cultural resources. HRC also evaluates properties for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places and conducts historic surveys and resource studies. One such study of Storer College in Harpers Ferry, the first college established for African Americans in West Virginia, is currently under way for the National Park Service. In 1999, HRC was awarded contracts to perform two major projects for the West Virginia Regional Jail Authority. Two years earlier, in evaluating property in Barboursville, which lies just east of Huntington, for the siting of a new regional jail facility, the Regional Jail Authority hired another company to conduct a "Phase I" archeological investigation of the area. "With the site at the confluence of the Guyandotte and Mud rivers, we had a feeling some Native American artifacts would be uncovered," says Steve Canterbury, executive director of the Jail Authority.

In its study, the company identified several sites with archeological features and artifacts and recommended additional testing to determine whether the sites were intact or had been disturbed. Disturbances, such as plowing, render sites less valuable as true archeological sites and ineligible for the National Register of Historic Places. In 1999, HRC was awarded a contract to conduct "Phase II" testing of the sites identified in the Phase I investigation. After several test excavations, HRC concluded that the sites had indeed been disturbed by plowing and the construction of a road. "Because where you find artifacts is so important, if they've been moved, the site is compromised," Gozdzik explains. "When things are removed from their context, we lose information that we need to interpret the site. It is no longer significant in terms of what it can tell us about the past."

Founding father William Merritt, who operated two grist mills in the village originally known as Merritt's Mill, was a former officer in the Revolutionary War. In April 1809, the first Cabell County Court met in his home on the left bank of the Mud River. While William Merritt is not thought to have been buried at the family cemetery, the site contained the graves of a number of his descendants, as well as that of Revolutionary War veteran Malchor Strupe. "We tried not to move the cemetery, but the alternative was to build an unsightly 20-foot-high wall around it," Canterbury notes. "That would have been more expensive than moving it." In October 1999, an HRC crew began relocation of the Merritt family graves. In order to photograph the area and accurately record the current location of headstones and footstones, brush and several large trees were removed. After the area was cleared, 15 buried headstone bases and stone fragments were found, in addition to the 25 visible headstones and 13 footstones.

Gozdzik and her staff had suspected that there were more graves inside the fenced boundary of the cemetery than were plainly visible, and that there were perhaps more outside the boundary, as well. Complicating their mission was the fact that some 10 years earlier, a well-intentioned Boy Scout troop had adopted the Merritt cemetery for an Eagle Scout project. The troop cleaned up the area, resurrected fallen headstones, and erected a fence around the grounds. By using several noninvasive evaluation methods, including ground-penetrating radar, HRC discovered that there were, in fact, 52 burials included in the Merritt cemetery, with 19 located outside the fence.

"When the Boys Scouts came in, they didn't do any archeology to find out where the actual graves were," Gozdzik says. "As we excavated, we discovered that where the scouts had put the headstones and footstones had no relation to where the burials were. They set them up in nice neat rows, but we found the burials in a little cluster here and a little cluster there." Examination of the headstones (many of which were deteriorated beyond legibility), historic research, and excavation of the cemetery uncovered the harsh reality of frontier life in the early 1800s. Of the 52 graves, nine are those of children and 10 are those of infants. The HRC crew carefully excavated each grave, removing the few contents that remained and placing each in a pine box for reinterment. "The coffins they were originally buried in were totally destroyed," Gozdzik says. "We wanted to stay as close as possible to the actual circumstances of the time, so we had boxes constructed of pine. We made them smaller, however. Everything we found in the grave went into that box and it was reinterred." Largely due to the acidity of the soil, most of the contents of the graves had returned to the earth. For the most part, all that remained were some teeth; an occasional button; some fabric, including a piece of hemp that may have been used to close a shroud; hardware, including coffin nails, hinges, and handles; and bottoms of shoes. "It was the frontier, so all the coffins were wood and the bodies were not embalmed," explains Bergeron. "It's not surprising, with these factors and the acidic soil, that there wasn't a lot left."

The remains of Revolutionary War veteran Malchor Strupe were reinterred later at a special ceremony. Unrolling a large map of the property, Gozdzik points to the original site of the cemetery and its new location. "We moved them from here to here," she notes. "They haven't been taken off the old homestead. There's a creek there and some trees and a holly bush. We tried to put the cemetery back the way it was when the family members were buried." "We tried to respect the past and did everything according to best practices," Canterbury says. "We replanted trees from the original site and we are looking for an old wrought iron fence to put around the cemetery." Stones at the end of the driveway leading up to the relocated cemetery will display bronze plaques identifying who is buried in the cemetery and why and when it was moved. "I think we've done the best we could," Canterbury adds.

About a month after HRC began excavation of the Merritt cemetery, Gozdzik and her crew realized that "prehistoric features," including artifacts, were present in the soil about two feet above the six-foot-deep graves. While the areas had been disturbed nearly 200 years ago by the burials and disturbed again by HRC's excavation, Gozdzik surmised that the areas within the cemetery where there were no burials may be a portion of an intact archeological site. After confirming with the West Virginia Division of Culture and History that further excavation was needed to determine whether the site was eligible for the National Register, in January 2000, HRC began systematic excavation in the northern part of the cemetery. In the January chill, using a painstaking and methodical process, 35 five-foot-square units, comprising more that a third of the undisturbed site area, were excavated. Gozdzik describes the process as "a very time and labor intensive kind of ordeal." "Every 10 centimeters you go down, you stop, you measure, you record, you photograph, and then you start over again," she says. "We can't do it quickly if we want to get the information." Excavation forms and an extensive photograph log of each excavation unit is kept while crews work in the field. Since each level of the unit is destroyed as the dig proceeds, the log allows crew members to recall the unit at any stage of the excavation process. While HRC uncovered a wide range of artifacts and a prehistoric fire pit, results obtained from the units proved that the sites had been disturbed, probably by plowing before the area became a cemetery. With the understanding that the property was not eligible for the National Register of Historic Places, excavation was halted. HRC did, however, collect hundreds of artifacts and take soil and charcoal samples for analysis. "Even though you would not call these artifacts diagnostic,' we need to take another look at them because they still provide information," Gozdzik says. While artifacts recovered from the site suggest that the area was occupied as early as the Early Archaic period, or as long as 10,000 years ago, the majority of the materials date from the Woodland period, which lasted from about 1000 B.C. to A.D. 1000. Evidence of hearths and fire pits were identified at the site, but no evidence of houses, suggesting that it was used as a short-term campsite by local Native American populations. When HRC's analysis of the artifacts is completed, Canterbury says, the ancient finds will be distributed to state university archeology departments, local museums, and local historical societies. "We'll rely on HRC for guidance as to where they will go," he adds. "But we want to put them where people can get the most use out of them." Gozdzik feels there is a need for a universal curation facility in the state where artifacts can be catalogued and stored for use by future archeologists and researchers. There is no shortage of artifacts to be discovered in West Virginia and added to the collection, she notes. And archeology students can learn all the skills they need right here in the state. Gozdzik and her staff, in conjunction with the WVU Sociology and Anrthopology Department, offer a six- to 10-week archeological field school for WVU students annually in Parkersburg. "I feel strongly that students should have the opportunity to do archeology here in the state," she says. "There's a lot of archeology to be done here. You don't have to travel to Colorado or Europe." A hands-on learning experience, the field school gives students a chance to set up a grid, dig an excavation unit, correctly record information, and wash and catalog artifacts. Students live and work together for the duration of the school. "It's very demanding," Gozdzik adds. "Students either decide they like archeology or it isn't for them." With more than 20 years in the business, Gozdzik still finds the science of archeology a stimulating and rewarding mental challenge. "It's like a jigsaw puzzle turned upside down," she muses. "We take the puzzle and turn the pieces up and follow what's under the ground. It's getting that first piece of the puzzle that's the hardest part." ----------------------------------------------------------------

The West Virginia Department of Natural Recourses and the Wild Wonderful

West Virginia Magazine has granted permission to reproduce the story

"Excavating Clues to the Past" by Sheila McEntee published in the March

2001 issue of Wonderful West Virginia Magazine. The purpose of this

request was to reproduce the article on Doors to the Past.

[ Cemetery ]

|

"You

can tell which part of the grave area is the human remains," adds Gozdzik.

"It's darker, organic matter. We placed that, along with the other contents

of each grave, into the reinterment containers."

"You

can tell which part of the grave area is the human remains," adds Gozdzik.

"It's darker, organic matter. We placed that, along with the other contents

of each grave, into the reinterment containers."